| Call for Papers: Special Issue on 'Generative AI meets Agent-Based Modelling and Simulation' |

| Credits: N/A |

|

Motivation: We are excited to announce a new Special Issue for the MDPI journal Algorithms. We are seeking innovative research that explores the transformative intersection of Generative AI and Agent-Based Modelling and Simulation (ABMS). As Large Language Models (LLMs) and generative technologies continue to evolve, they offer unprecedented opportunities to enhance the entire ABMS workflow, from conceptualisation and code generation to stakeholder reporting. However, this integration also brings critical challenges regarding transparency, validation, and ethics that the research community must address. |

|

|

Scope:

Topics:

Guest Editors:

Submission Details:

More Information: Read more and submit your work here. Keywords: #GenerativeAI #AgentBasedModelling #ABM #Algorithms #Large Language Model #LLM #Simulation #ComputationalSocialScience #DecisionSupport #SpecialIssue #ResponsibleAI #Research |

| Back to Top |

| LLM4ABM Special Interest Group (SIG) Established as an ESSA SIG |

| Credits: Peer-Olaf Siebers |

|

As a recent addition to the ESSA (European Social Simulation Association) Special Interest Group (SIG) portfolio, the LM4ABM (Large Language Models for Agent-Based Modelling) SIG explores the latest trends in applying LLMs within the context of Agent-Based Modelling (ABM) Our Mission:

What we do:

Join Us! Everyone is welcome - newcomers and experts alike. Organiser: Peer-Olaf Siebers (University of Nottingham, UK) If you would like to join, email me at peer-olaf.siebers@nottingham.ac.uk |

| Back to Top |

| LLM Support for Creating RAT-RS Reports (2/2): Quality & Reliability |

| Credits: Conceptualisation, experimentation and drafting by Peer-Olaf Siebers. Copy editing and initial output analysis by Claude Sonnet 4.5 |

| Motivation |

|

In my previous blog post "LLM Support for Creating RAT-RS Reports" I wrote about the potential of using LLMs for generating draft RAT-RS reports. In short, the RAT-RS is a reporting standard intended to improve documentation of data use in Agent-Based Modelling (ABM). It supports reporting across several data applications (specification, calibration and validation) and is compatible with a variety of data types, including statistical, qualitative, ethnographic and experimental data, consistent with mixed methods research (Achter et al 2022). Structured as a set of Question Suites (QSs), the RAT-RS addresses distinct phases of data use throughout the ABM lifecycle. For this blog post I wanted to find out more about the quality of these LLM-generated draft RAT-RS reports. To guide this exploration, I formulated two distinct hypotheses based on the distinction between objective and subjective content:

Besides testing these hypotheses I was also interested in exploring the response similarity of different LLMs in comparison to the human-authored RAT-RS report, as well as the similarity between responses from the same LLM when answering objective and subjective questions. I opted to bypass a comprehensive review of the extensive literature on human versus LLM question answering and quality measurement. While plenty of academic studies exist for those wishing to dive deeper, my primary motivation was to explore these dynamics through direct, hands-on experimentation. A spreadsheet containing all figures in this blog post, as well as the source code for the semantic analysis tool, is available for download. |

| Question Objectivity Classification |

|

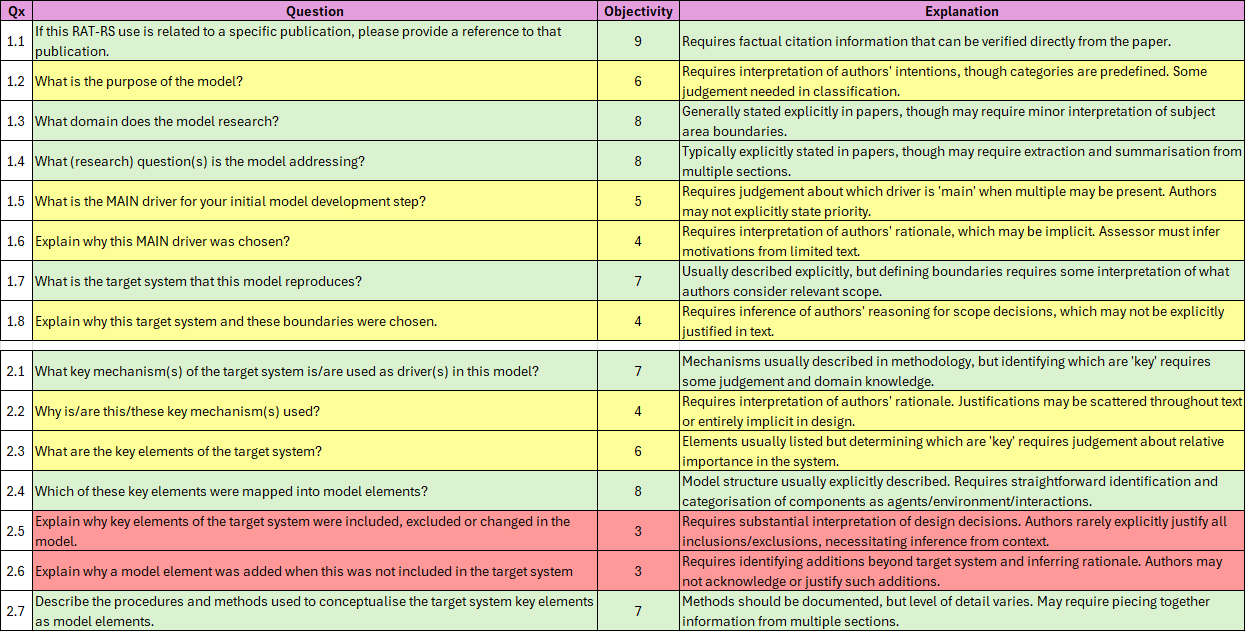

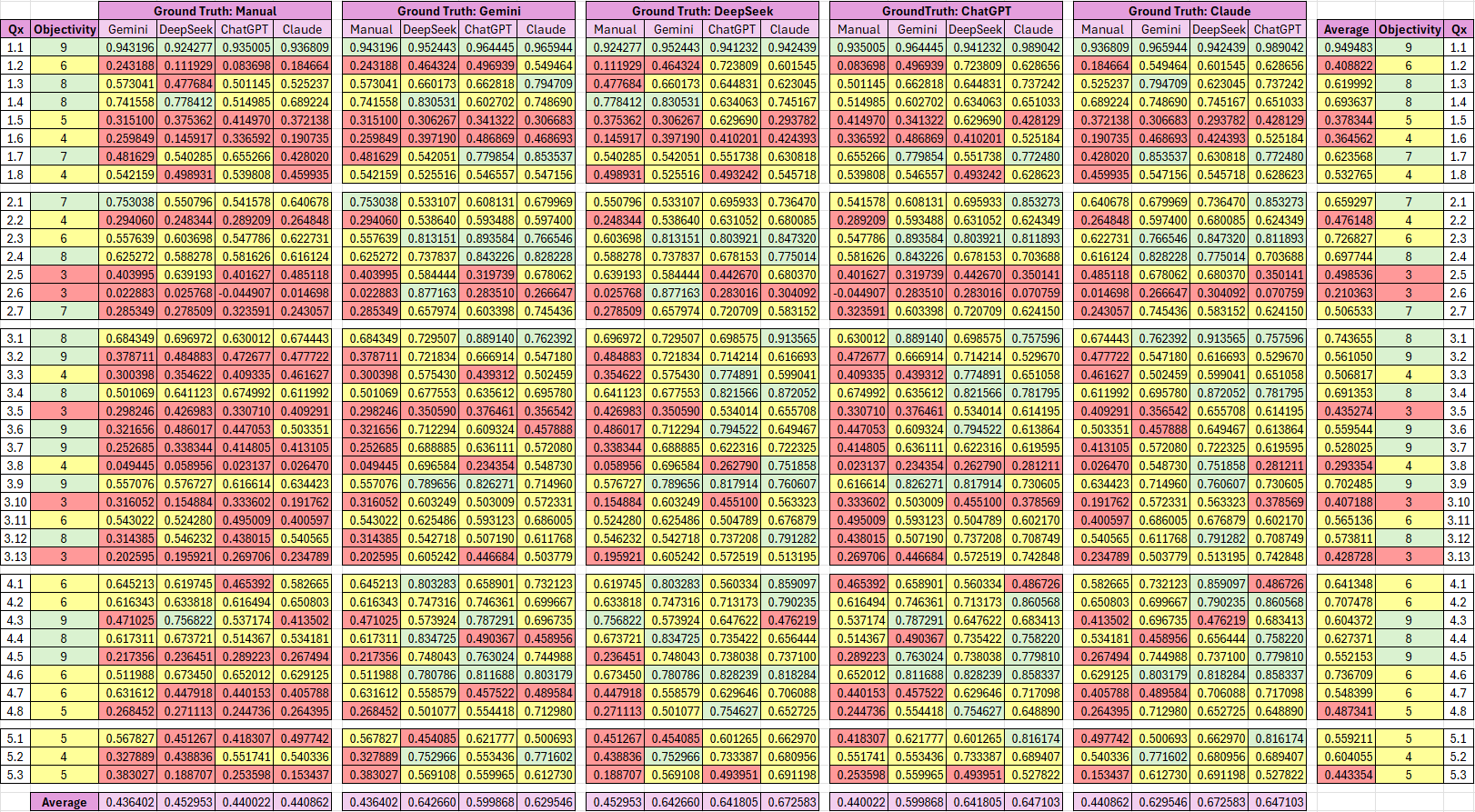

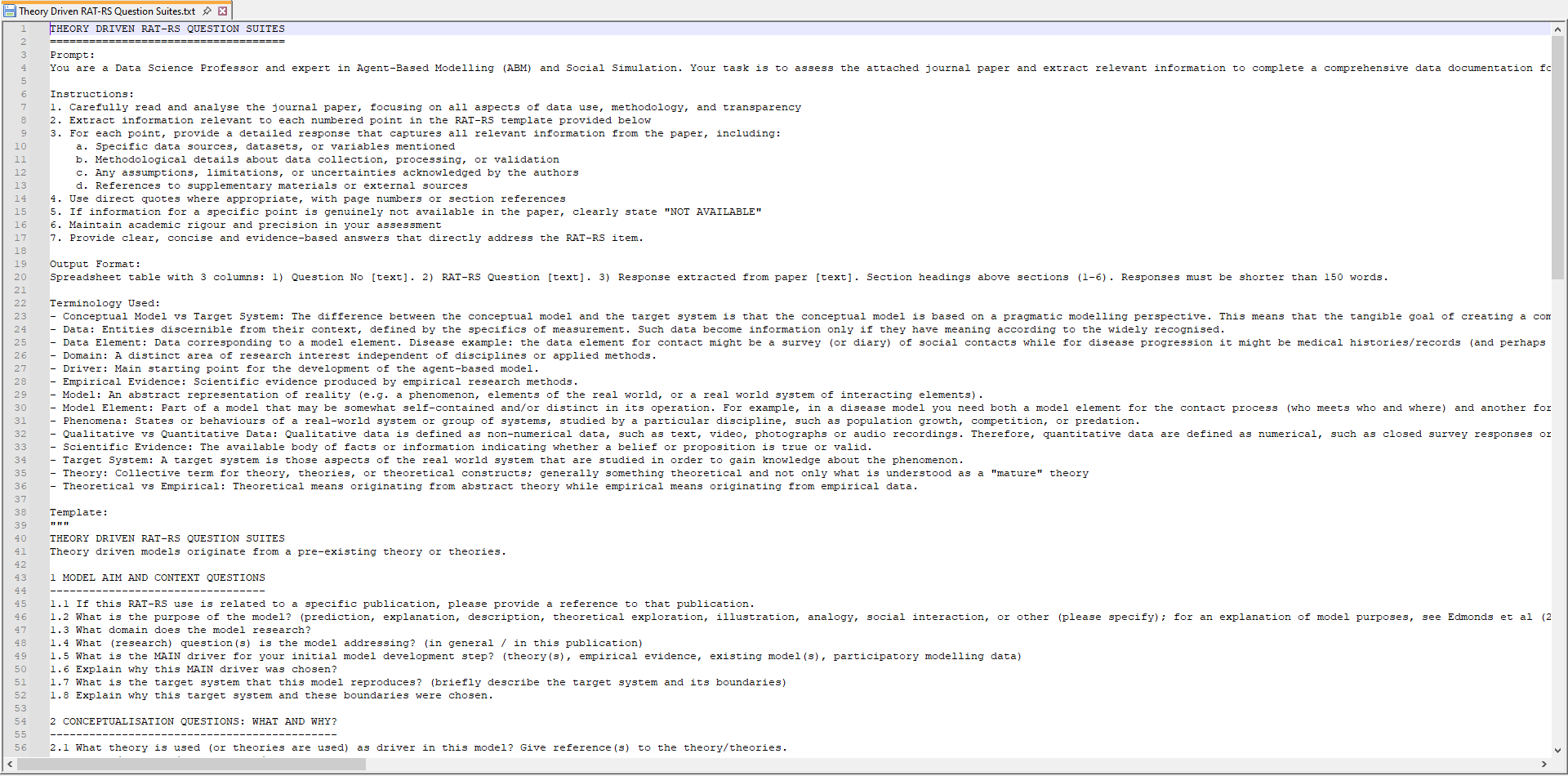

I started by analysing the "Question Objectivity" of the RAT-RS questions. In our case question objectivity refers to the degree to which a question has a single, verifiable answer that can be directly extracted from source material without requiring interpretation, inference, or evaluative judgement. The objectivity classification provides a foundation for interpreting the subsequent experiments. It establishes a framework for understanding whether response patterns correlate with question characteristics.

I asked Claude to do the job for me and to conduct a classification of all RAT-RS questions, categorising them into three categories, to keep it simple: objective questions (objectivity level 7-9; green in the below table), moderately subjective questions (objectivity level 4-6; yellow in the below table), and highly subjective questions (objectivity level 1-3; red in the below table). I then checked the classification and found that the criteria have been well applied and that the explanation provided feasible justifications for the decisions. The result is shown below. |

|

| Click images to enlarge |

|

| Click images to enlarge |

|

| Click images to enlarge |

|

The analysis shows that QS 1 to QS 5 contain a mixture of objective fact-extraction and moderate interpretation questions, whereas QS 6 consists of a set of highly subjective questions that require assessors to apply expert judgement to evaluate quality and provide recommendations. QS 6 was added solely to test how LLMs handle the type of questions contained in this QS. It is not part of the original RAT-RS and is therefore not used when judging the quality of automatically generated RAT-RS reports. |

| Similarity Assessment via Semantic Analysis |

|

The next step in this project was to look at Similarity Assessment via Semantic Analysis. While my initial quality assessment was based on (my own) expert opinion, this time I want to use a scientific approach. For the similarity assessment I used the paper by Siebers & Aickelin (2011) that I already used in the previous blog post. Semantic analysis via sentence similarity provides a quantitative method for assessing the semantic equivalence and content relatedness between textual units. The primary technique employs sentence embedding models (e.g., SBERT, Universal Sentence Encoder) that encode a sentence into a dense, high-dimensional vector representation, which mathematically encapsulates its semantic meaning. The similarity between two sentences is then computed by measuring the geometric distance between their corresponding vectors, most commonly using cosine similarity. A cosine score approaching 1.0 indicates high semantic congruence. For the assessment, I used a custom semantic analysis tool I developed with Gemini's assistance. The tool leverages the SBERT sentence embedding model to enable several analytical capabilities: comparing two individual RAT-RS reports, calculating individual and average quality statistics, and facilitating human question-by-question comparison through a side-by-side response display. Importantly, the tool supports both inter-response analysis (comparing reports across different LLMs) and intra-response analysis (comparing multiple reports generated by the same LLM). I conducted both inter-response and intra-response semantic similarity comparisons. This approach allowed for an evaluation of both alignment between different sources and the inherent consistency of each model. In the inter-response evaluation, I compared the semantic similarity between RAT-RS reports from different sources, included a human-authored RAT-RS report and generated reports from four distinct LLMs. In the intra-response evaluation, I assessed the consistency of each individual of the four LLMs included in the analysis by comparing the semantic similarity across three of their own distinct responses to the same prompt. For both, I examined the association between question objectivity and response similarity. |

| Inter-Response Semantic Similarity Comparison |

|

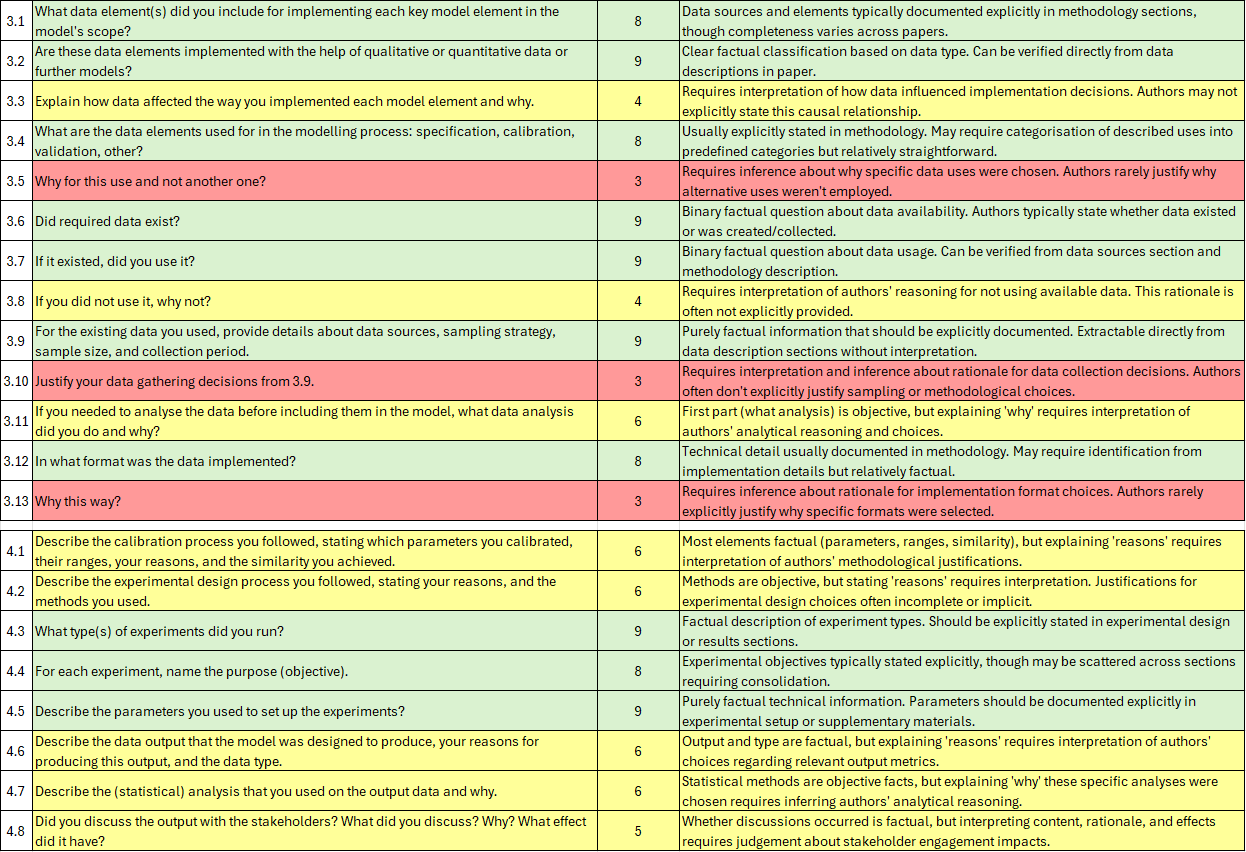

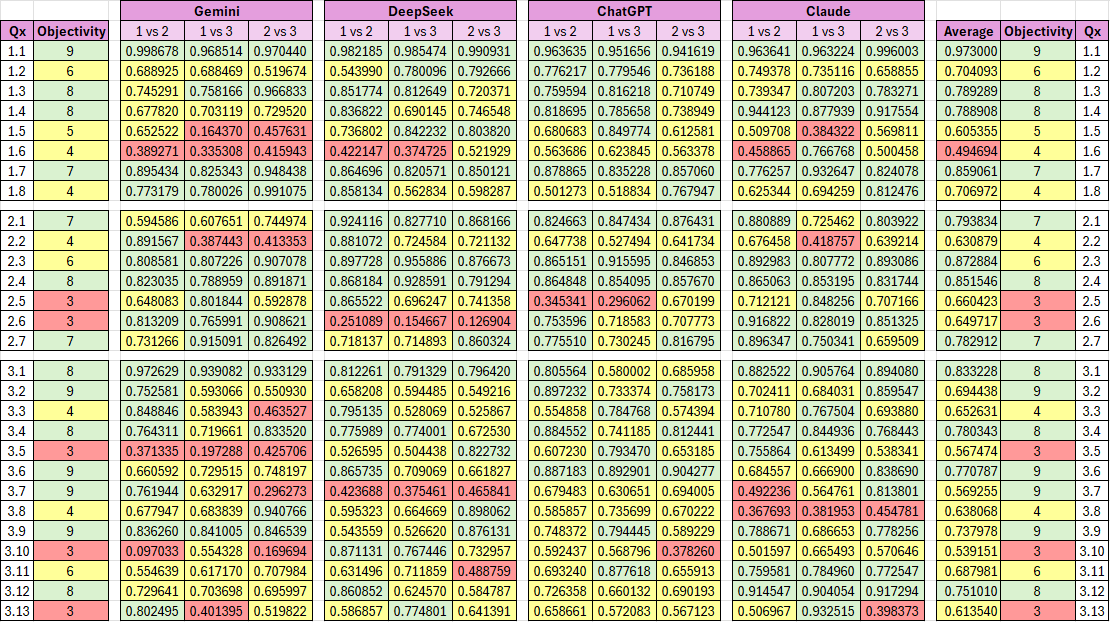

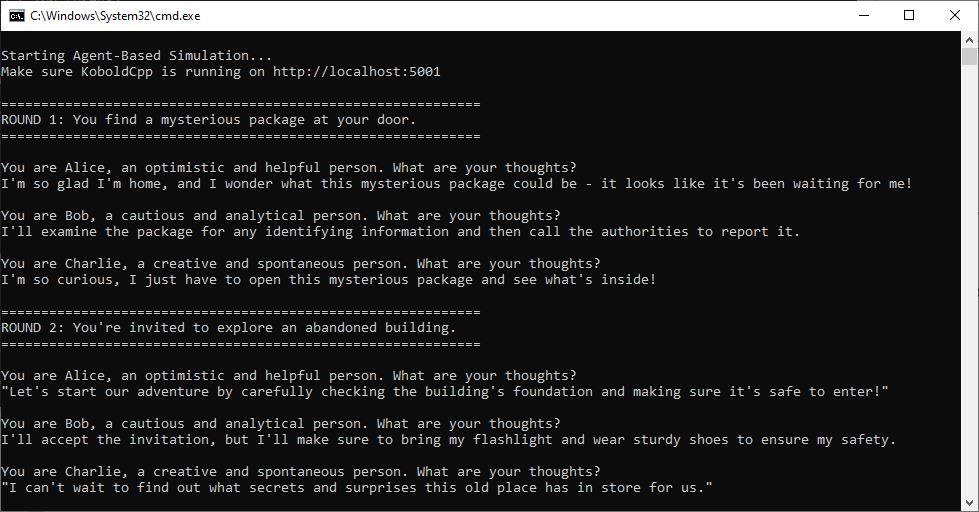

For the inter-response semantic similarity comparison I copied the human-authored RAT-RS report and the responses of the four LLMs included in the analysis into the same spreadsheet. As the human-authored RAT-RS report was lacking QS 6, I ignored this QS as well for this analysis. The primary metric used for assessing the similarity between different interpretations of the same document is cosine similarity, which measures the angle between two text vectors in high-dimensional space. With this approach we capture semantic relatedness rather than exact word matching. The cosine similarity score can take on values between 0 and 1. A rule of thumb for assessing the similarity between texts is the following:

In the experiment I calculate the similarity between human-authored and LLM generated RAT-RS reports. As we don't know which of the reports provides the best quality answers, I have collected data for each of the reports being the ground truth that other reports are compared to. The results can be found below. To keep it simple I reduced the number of categories to three: strong agreement (similarity score 0.75-1.00; green in the below table), moderate agreement (similarity score 0.50-0.75; yellow in the below table) and weak agreement (similarity score 0.00-0.50; red in the below table). |

|

| Click images to enlarge |

|

The human-LLM similarity comparison reveals modest semantic alignment between the human-authored RAT-RS report and LLM-generated versions, with all models achieving similarity scores between 0.436 and 0.453, indicating weak to moderate agreement according to the established interpretation framework. This suggests substantial interpretive divergence in how different sources address the same research paper, potentially reflecting fundamental differences between human expert knowledge synthesis and algorithmic text processing approaches. The relatively low scores imply that LLMs and human experts prioritise different textual elements or employ distinct interpretative strategies when extracting information from academic literature. It is also interesting to see that some questions that have been previously classified as highly objective (e.g. Q3.2 and Q3.7) do very poorly in the human-LLM similarity comparison, being in only in weak agreement. In contrast, the inter-LLM similarity comparisons show considerably stronger semantic convergence, with pairwise similarities ranging from 0.600 to 0.673, demonstrating moderate to strong agreement. DeepSeek and Claude exhibited the highest inter-model similarity (0.673), whilst Gemini and ChatGPT exhibited the lowest inter-model similarity (0.600). These patterns suggest that whilst LLMs converge towards similar interpretative frameworks distinct from human expert analysis, individual model architectures, training methodologies, and underlying datasets still produce measurably different semantic outputs when processing identical source material. This clustering effect, where LLMs resemble each other more than the human baseline, raises important questions about whether automated RAT-RS report generation captures the nuanced understanding that domain experts bring to documentation tasks, or whether it simply reflects common training data biases across contemporary language models. However, it is also plausible that lower similarity might reflect the human extraction capturing fewer details rather than interpretative divergence. If the human-authored RAT-RS report provided more succinct answers whilst LLMs generated RAT-RS report provided more elaborate responses with additional contextual information, this would mathematically decrease similarity scores despite both being "correct" interpretations. However, expert responses typically exhibit higher information density rather than lower detail levels. Domain experts often include tacit knowledge and nuanced interpretations that LLMs might miss, suggesting the low similarity might genuinely reflect interpretative differences rather than brevity alone. Returning to Hypothesis 1 that LLMs align with humans on objective questions but diverge on subjective ones, the averages on the right of the table suggest a correlation between objectivity and similarity of responses. Most questions classified as subjective score low in the average similarity. This supports the hypothesis that while LLMs can retrieve factual data somewhat reliably, their interpretative strategies for subjective queries differ fundamentally from those of human experts. The next step would be to conduct an in-depth direct comparison and expert judgement of each individual question by an expert, ideally the author of the paper under investigation. This will show which of the above hypotheses are correct, and if the automated extraction works better than the semantic analysis suggest. |

| Intra-Response Semantic Similarity Comparison |

|

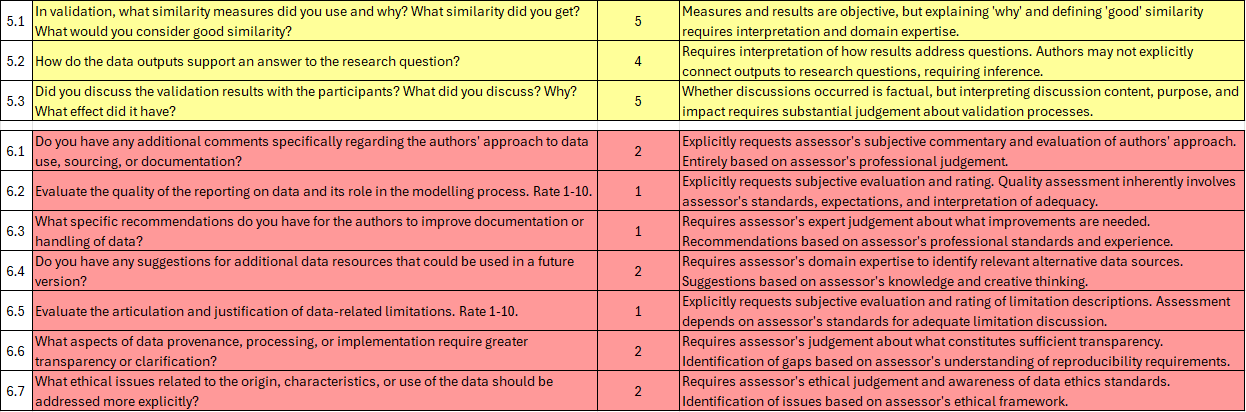

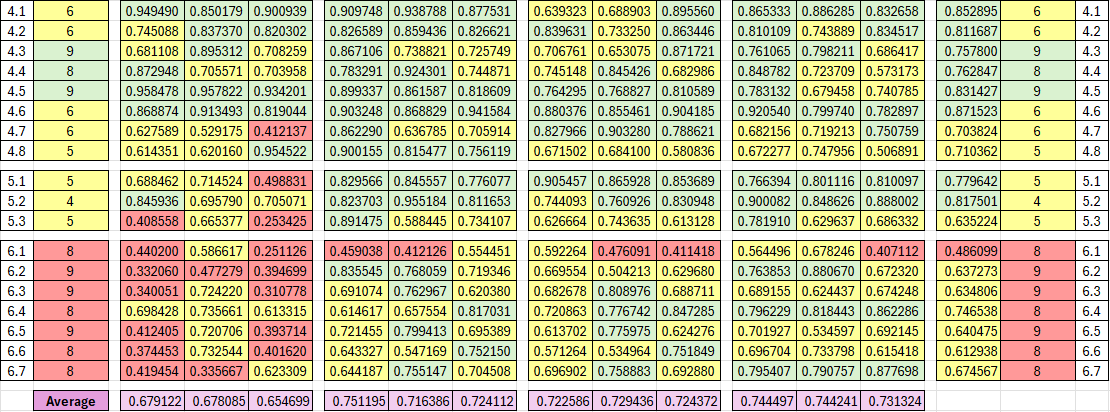

For the intra-response semantic similarity comparison I copied three RAT-RS response reports per LLM into a single spreadsheet for each of the four LLMs included in the analysis. In the analysis I calculated the similarity between LLM generated RAT-RS report replications for all four LLMs. The results can be found below. Of course the intra-response similarity relies heavily on LLM settings such as Temperature and Top_p value, affecting output determinism. Unfortunately, there are no reliable information available from the LLM companies. My best guess is that LLMs would have similar default settings with regards to temperature and top_p values for their public facing interfaces. On could run the experiments using controlled experimental conditions by using API access, but I leave this for the future. |

|

| Click images to enlarge |

|

| Click images to enlarge |

|

There is no systematic pattern emerging from the intra-response similarity analysis. However, two observations stand out. First, inconsistency associated with question subjectivity is dispersed across the entire set of question rather than concentrated in specific questions. This is unexpected. If subjectivity were the dominant driver, one would expect similar questions to exhibit higher inconsistency across all models. Instead, the locations of lower similarity differ by LLM, indicating that response instability is model-specific rather than question-specific. Second, Gemini exhibits substantially higher intra-LLM inconsistencies than any of the other models, most notably for the highly subjective QS 6. This behaviour is not mirrored by DeepSeek, ChatGPT, or Claude, which remain comparatively stable even on highly subjective questions. The average intra-response similarity scores further reinforce these differences. Gemini records the lowest mean similarity (0.671), whereas the remaining three models cluster closely together (DeepSeek: 0.731; ChatGPT: 0.725; Claude: 0.740). Claude demonstrates the highest overall consistency. Notably, all averages except Gemini lie just below 0.75, which marks the transition to strong semantic similarity. This suggests that, under default interface settings, most models produce reasonably stable responses to repeated prompts, with Gemini as a clear outlier. Returning to Hypothesis 2 that subjective questions would result in poor consistency, the intra-LLM analysis provides no evidence of a relationship between question objectivity and response similarity. Subjective questions are not systematically associated with lower intra-model consistency. Instead, response stability appears to be driven primarily by model-specific generation behaviour rather than by the epistemic characteristics of the questions themselves. For example, Gemini exhibits substantially higher intra-LLM inconsistencies than any of the other models, most notably for the highly subjective QS 6, whereas Claude demonstrates high stability across both objective and subjective types. This fails to support Hypothesis 2; consistency is a feature of the model architecture and settings, not necessarily the subjectivity of the prompt. |

| Conclusion |

|

This study examined the quality and consistency of human-authored and LLM-generated RAT-RS reports, with particular attention to the relationship between question objectivity and response similarity. The primary takeaways from this investigation are:

Overall, LLMs can support the generation of RAT-RS reports but cannot replace expert judgement. They produce coherent and often detailed outputs, yet their interpretations differ systematically from human experts and vary across models. Used with appropriate oversight, they are a valuable assistive tool, not an authoritative one. |

| References |

|

| Appendix |

|

This appendix presents additional exploratory experiments conducted during the study. While these do not directly address the stated hypotheses, they provide useful context and insights into the behaviour of the models and the broader experimental setup. |

| Question Order Bias |

|

After creating many reports I observe a consistent pattern across different LLMs and papers: Question 6.5 (limitations articulation) consistently scored higher than Question 6.2 (overall data reporting quality). I asked Claude for an explanation, and Claude came up with some suggestions that provide some food for thought.

So, the suggestion is that the pattern indicates paper authors are better at acknowledging gaps than preventing them, which RAT-RS exists to address! For testing the above hypotheses, Claude suggested to swap the two questions, asking Question 6.5 before Question 6.2 and see if the pattern persists. And in fact, applying the suggestion of swapping the questions broke the pattern. This is a practical demonstration of the principles of complexity theory: the scoring pattern emerged from the interaction between question sequence and the LLM's contextual reasoning. A small intervention altered this network of influences, shifting the outcome. While it is exciting to see complexity theory in action, it is equally concerning. It forces me to consider how many other latent structural biases may be hidden within the RAT-RS framework. It's a critical insight for any research methodology employing sequential or interdependent evaluation criteria. |

| Testing Claude's Patience |

|

I wanted to see, what happens if I feed in unrelated literature. I chose a "Lorem Ipsum" paper and "'I Shall Sing of Herakles': Writing a Hercules Oratorio for the Twenty-First Century", written by Emma Stafford and Tim Benjamin. Testing Claude using a Lorem Ipsum paper showed that Claude correctly identified the paper as placeholder text rather than a genuine research article. The ranking of quality was 1/10 for both Question 6.2 and Question 6.5. At the end, Claude sounded a little grumpy, providing the following conclusion:

Testing Claude using Poetry revealed that Claude immediately identified the absence of any model in the paper and repeated this observation in response to every question. The ranking of quality however was 5/10 for Question 6.2 and 8/10 for Question 6.5. The comments for these stated that the scores assessed the humanities content of the paper, as the paper had nothing to do with ABM. However, this time Claude was less grumpy and provided the following conclusion:

|

| Back to Top |

| LLM Support for Creating RAT-RS Reports (1/2): Feasibility |

| Credits: Written by Peer-Olaf Siebers. Copy-edited by ChatGPT 5 |

| Motivation |

|

When we report research outcomes, we should provide clear, accessible information about our data: what data we used, why we used it, and how we used it. This strengthens readers' understanding and supports reproducibility. In practice, however, those details are scattered throughout publication and are rarely easy to find. Although the Agent-Based Modelling (ABM) community has a reporting standard, the Rigor And Transparency Reporting Standard (RAT-RS), uptake has been limited. Colleagues and I agree that the main barrier is effort. Producing a RAT-RS report feels time consuming, especially for smaller projects, and there is a sense that others do not bother either; a classic "Tragedy of the Commons". My goal was to test whether Large Language Models (LLMs) can do the heavy lifting of extracting the required information from publications so that humans need only validate and refine the output. Large language models are good at text extraction and summarisation, so they are a natural fit for this task. I wanted to evaluate their reliability in assisting this workflow. |

| What is the RAT-RS |

|

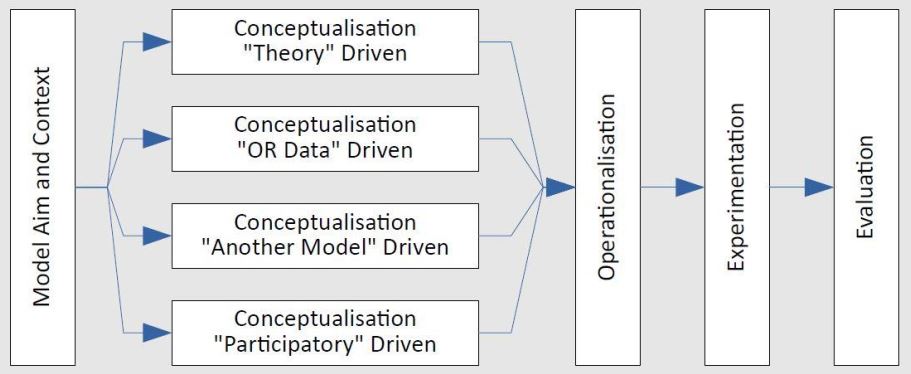

The RAT-RS is a reporting standard that emerged from a Lorentz Center Workshop on Integrating Qualitative and Quantitative Evidence using Social Simulation (Leiden, the Netherlands, April 2019) and was refined across subsequent workshops, until it was finally published in Achter et al (2022). The RAT-RS is intended to improve documentation of data use in ABM. It supports reporting across several data applications (specification, calibration and validation) and is compatible with a variety of data types, including statistical, qualitative, ethnographic and experimental data, consistent with mixed methods research. The RAT-RS is organised as a Question Suite (QS) toolbox. Each QS focuses on a distinct aspect of data use. There are multiple RAT-RS "flavours" with distinct Conceptualisation QSs. The first step in applying the RAT-RS is to identify the main driver of model development. The RAT-RS supports four approaches: theory-driven models (focusing on pre-existing theories), OR-data-driven models (focusing on key mechanisms), another-model-driven models (focusing on pre-existing models), and participatory-driven models (focusing on participatory design processes). |

|

| Click image to enlarge |

|

As an example, here are the questions from the Operationalisation QS:

For full details see Achter et al (2022). |

| The Magic Prompt |

|

I used an exploratory approach for crafting the prompt needed to extract relevant RAT-RS information from publications. Surprisingly, I found that the information extraction works better without providing a reference to the RAT-RS publication. Instead, a concise summary of the RAT-RS and its terminology improved responses. Including the terminology definition in the prompt made a notable difference. The prompt itself consists of separate components to provide clear guidance to the LLM on what is expected from it in terms of response delivery. The prompt is modular and contains the following components:

Providing the definition of the terms used in the RAT-RS QSs made a big difference. |

|

| Click image to enlarge |

|

Two elements I experimented with were a request to include direct quotes with page or section references to aid validation (Instruction component), and a strict word limit for each response to prevent verbosity. Claude, for example, became very verbose without a word limit (Output Format component). I recommend testing these options and adjusting them to suit your specific needs. I also created a supplementary QS that asks the LLM to assess reporting quality and to make recommendations to the authors for improving data use, sourcing and documentation. Initially this was an informal experiment to see how the LLM evaluated the authors' efforts. However, the responses were sufficiently insightful that I incorporated it as QS6 in the RAT-RS. The full prompt template for each individual RAT-RS flavour is available on GitHub. |

| To download the source code from GitHub, click the "Code" link above. This will take you to the correct section of the GitHub repository. In the window that opens, click the downward-facing arrow in the top-right corner to download the zip folder containing the prompts and examples. The folder will be saved to your default download location. |

|

|

To use this novel LLM supported method for generation RAT-RS reports, choose the RAT-RS flavour most relevant for the publication, select an LLM (ideally using an advanced mode), upload the publication, copy and paste the prompt template, and run the query. The LLM will produce a draft RAT-RS report that you can validate and refine. It's as simple as that! |

| First Experience with Using LLMs to Generate RAT-RS Reports |

|

I tested the approach on the two worked examples included with the RAT-RS publication. These were useful because manually extracted reports from the original publication provide ground truth. The two examples were:

I tested four LLMs, using their advanced modes when they were free to use: Gemini (Thinking Mode), DeepSeek (DeepThink), ChatGPT (Think), and Claude (Standard). The LLMs showed clear differences in style, level of detail and response format. Two illustrative comparisons follow. The first example demonstrates variation in the level of detail and the tendency of some LLMs to omit quotations and page references, even though the prompt requested them. Q3.12: In what format was the data implemented? {e.g. look-up table; distribution}

The second example illustrates a case in which my manual extraction was somewhat cursory, whereas all of the LLMs produced far more detailed and thorough outputs. Q4.1: Describe the calibration process you followed, stating which parameters you calibrated, their ranges, your reasons, and the similarity you achieved.

Overall, the LLMs rarely produced completely incorrect answers. They often extracted useful details that I had missed during manual extraction, particularly when information was scattered through the paper. It is worth noting that one of Claude’s strengths was its ability to provide accurate quotations and page numbers, which makes validation straightforward. The trade-off is verbosity. More verbose outputs are less immediately clear. A full set of responses for all LLMs in form of two spreadsheets is available on GitHub. |

| To download the source code from GitHub, click the "Code" link above. This will take you to the correct section of the GitHub repository. In the window that opens, click the downward-facing arrow in the top-right corner to download the zip folder containing the prompts and examples. The folder will be saved to your default download location. |

|

| Use Cases for LLM-Generated RAT-RS Reports |

|

LLM-generated RAT-RS reports have several practical uses. They are not limited to publications and can also be applied to funding proposals, project notes and other documents. For authors, they can provide a first draft of data documentation, help validate data use and identify reporting gaps, support calibration by prompting follow-up questions after a draft RAT-RS report is produced, and act as a pre-submission check to ensure that required data details are included. For readers, these LLM-generated reports can offer a quick summary when data documentation is incomplete or missing and provide an easy way to compare data use across documents. For reviewers, they can give a concise overview of data use to support the assessment of the publication under review. For RAT-RS developers, they can reveal potential misinterpretations of questions that would require refinement, as well as misinterpretations of terminology that would require clearer definitions within the prompt. They can also help to identify redundant questions and duplicated reporting items and allow meta-researchers to analyse patterns of missing information across multiple papers. |

| Best Practice for Using LLMs to Generate RAT-RS Reports |

|

Using LLMs for RAT-RS report generation requires the same caution recommended in my earlier post on Publisher Policies for AI Use in Preparing Academic Manuscripts. As creating these reports is typically not part of the core research activity, it is legitimate and even encouraged to use LLMs for this task, provided that the LLM contribution is acknowledged and the output is validated by a human. Key points:

|

| Conclusion |

| Overall, the results of this experiment are very promising. LLMs show significant potential for generating draft RAT-RS reports, and there are numerous other use cases, as outlined earlier, that could be explored. I hope that integrating LLMs will make the RAT-RS more accessible and practical, helping to address the longstanding problem of insufficient documentation of data use in ABM publications, the very issue that motivated the development of RAT-RS. |

| References |

|

| Back to Top |

| The Generative ABM Experiment (1/3): From Concept to First Prototype |

| Credits: Concept, draft text, and cross validation by Peer-Olaf Siebers. Advice and copy-editing by Claude Sonnet 4.5 |

| Welcome! |

|

How do you actually integrate LLMs to make agents in social simulations mimic human-like decision-making behaviour? That is the practical challenge we are tackling in this new blog series.

Welcome to the Generative Agent-Based Modelling (GABM) experiment! In the next three blog posts I will discuss my attempt to implement my own GABM from scratch, based on the concepts described in my previous post. I will explain how I approached the tasks, what I learned from it, and what needs to change in future iterations. The planned blog posts are:

|

| Purpose |

| This first post focuses on the foundations. Here, I will describe the development of a first functional prototype. By prototype I mean an abstract and minimal version of the intended application. It must run and produce some kind of "meaningful" output. It is an exploratory tool that allows one to understand how things work and what I must pay attention to in the next development stages. |

| VIBE Coding |

| To build this quickly, I used an approach called VIBE coding. Instead of writing every line of code by hand, I described what I wanted in plain English to the LLMs I used for the conversation: Claude Sonnet 4.5 and DeepSeek-V3. These LLMs then generated the required Python code on my behalf. This is a fantastic way for rapid prototyping: you focus on the "what" and the "why", and the AI helps with the "how". The catch? You are likely to get bloated code and may not fully understand every line that is generated, but for a first prototype, the priority is to get something that works. |

| Using LLMs Locally |

|

For LLM-driven agent communication I deployed a local LLM using KoboldCPP 1.98.1. KoboldCPP is an easy-to-use, free and open-source text generation tool that allows users to run LLMs locally. Running a model locally keeps all conversations private, since nothing leaves the machine. It also allows for unlimited API usage free of charge. Execution is straightforward. After downloading the KoboldCPP executable (scroll down to "Assets" on the release page) it can be launched from the command line using its default settings. The only required input is the model file. Smaller models run faster, but this may reduce output quality. I say "may" because I have not tested the effect yet.

My "lab" setup was pretty modest: a desktop from 2018 with an Intel i5 processor, 2 GB of VRAM and 8 GB of RAM, running Windows 10 (x64). After trying out a few different models and different model sizes I decided to go for "qwen2.5-1.5b-instruct-q6_k.gguf" (1.5 GB) for my initial exploratory experiments. The model is available on Hugging Face. Which model works best for you depends, of course, on your computer specs. To run KoboldCPP in the terminal window we can use the command "koboldcpp --model qwen2.5-1.5b-instruct-q6_k.gguf --port 5001", assuming that the model is stored in the same folder as KoboldCPP. |

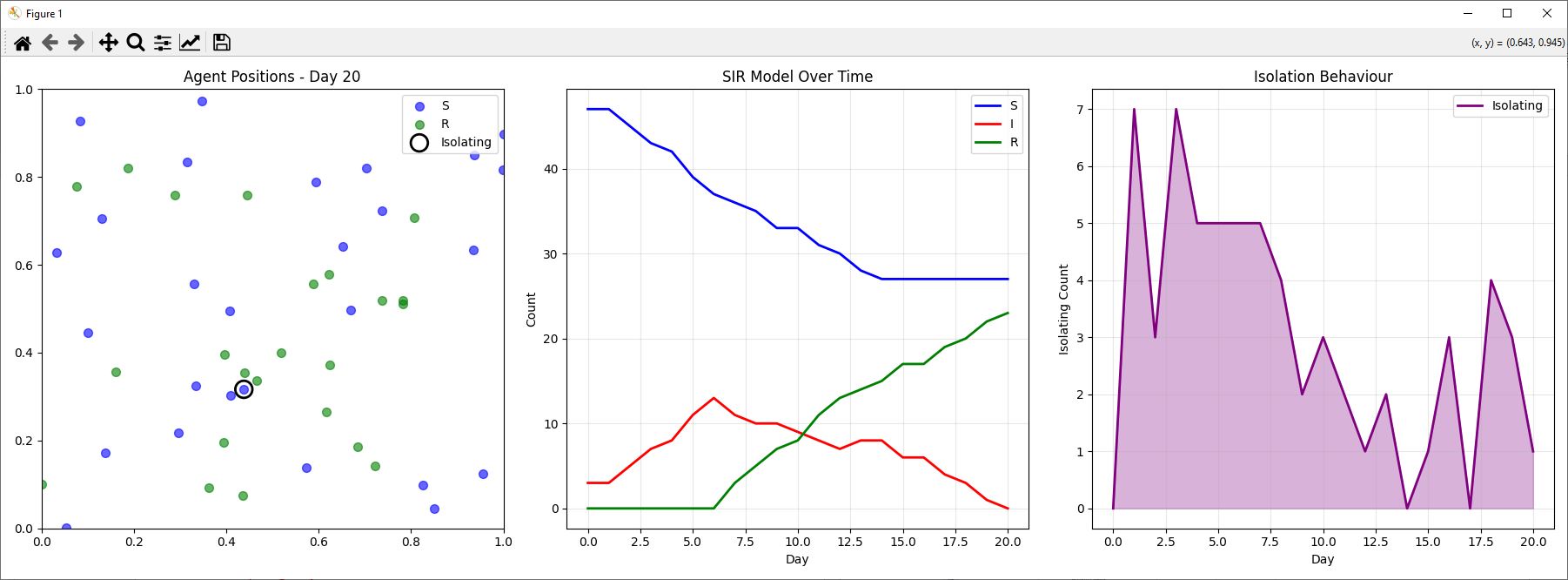

| Bringing Agents to Life Through LLM Dialogue |

| I started with a very simple Python script where for a few agents, each with their own personality, we could send questions to the local LLM and get personalised agent responses. With KoboldCPP running in one terminal window and my Python script in another, the stage was set. |

|

| Click image to enlarge |

| Communication worked! This marked the first real milestone :). |

| The Experiment: An AI-Powered Epidemic Model |

|

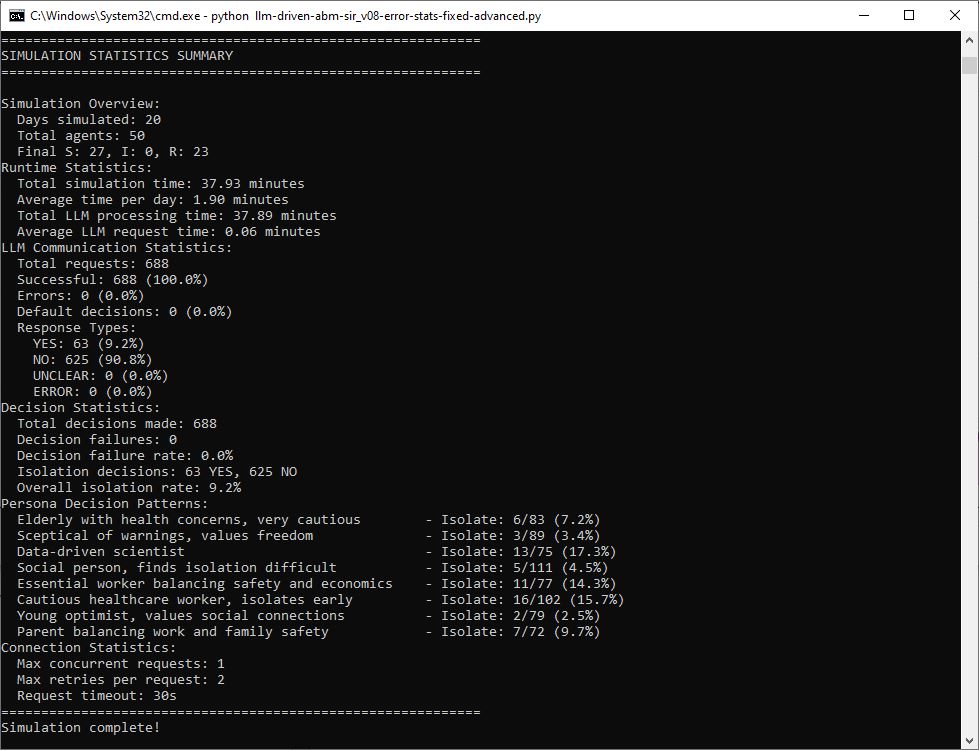

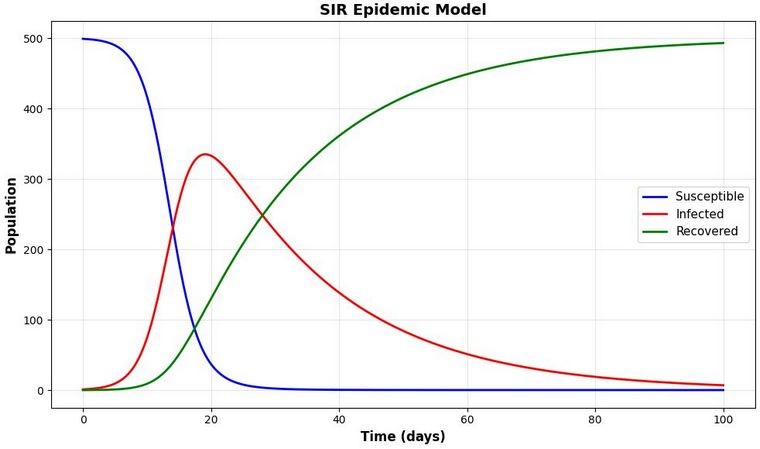

With basic communication working, it was time for a real test. I chose a classic Agent-Based Model, the SIR model, which simulates how a disease like COVID-19 spreads through a population, with people transitioning between "susceptible", "infected", and "recovered" state.

The twist? Instead of agents following pre-defined rules for decision-making, I tasked the LLM with making decisions on their behalf. The scenario: "Should a healthy agent decide to self-isolate based on its personality and the number of infected people nearby?" Here is the pseudocode of the LLM-driven decision process: |

Example interaction:

|

|

| Click image to enlarge |

|

| Click image to enlarge |

| The "It Looks Right, But Is It?" Problem |

|

Looking at it from a macro-level perspective, everything looked fine. However, looking carefully at the micro-level via the communication log, it turned out that many of the log entries contained some contradictory information about persona, decision, and reasoning. This brings us back to a typical LLM phenomenon: something looks right on the surface as it is presented in fluent natural language, but when we dig deeper we realise that it is not. The log also showed that quite a few decisions were based on the fallback rules used when communication and transmission errors occurred.

Here is an example where the response contains fundamental contradictions upon closer inspection.

Avoiding transmission errors requires fine-tuning (calibration) of the parameters controlling the LLM operations, such as the prompt and response length, the chosen LLM, and ensuring that we have sufficient computing power and memory. |

| Conclusions |

|

This first prototype achieved its main goal: we have a collection of agents independently communicating with an LLM for decision support and we have a working simulation model. We cannot expect a fully robust decision-support tool after just two weeks of evening work! What is good about this prototype is that it does not crash (it has a sophisticated error handling framework) and communication runs smoothly, as long as the number of concurrent requests is kept at an appropriate level (three with my machine). The prototype has proven to be very helpful for exploring how to build such GABMs in principle and where the pitfalls are. The logging system and the stats displayed at the end of a simulation run are very helpful when validating the model at both micro and macro levels.

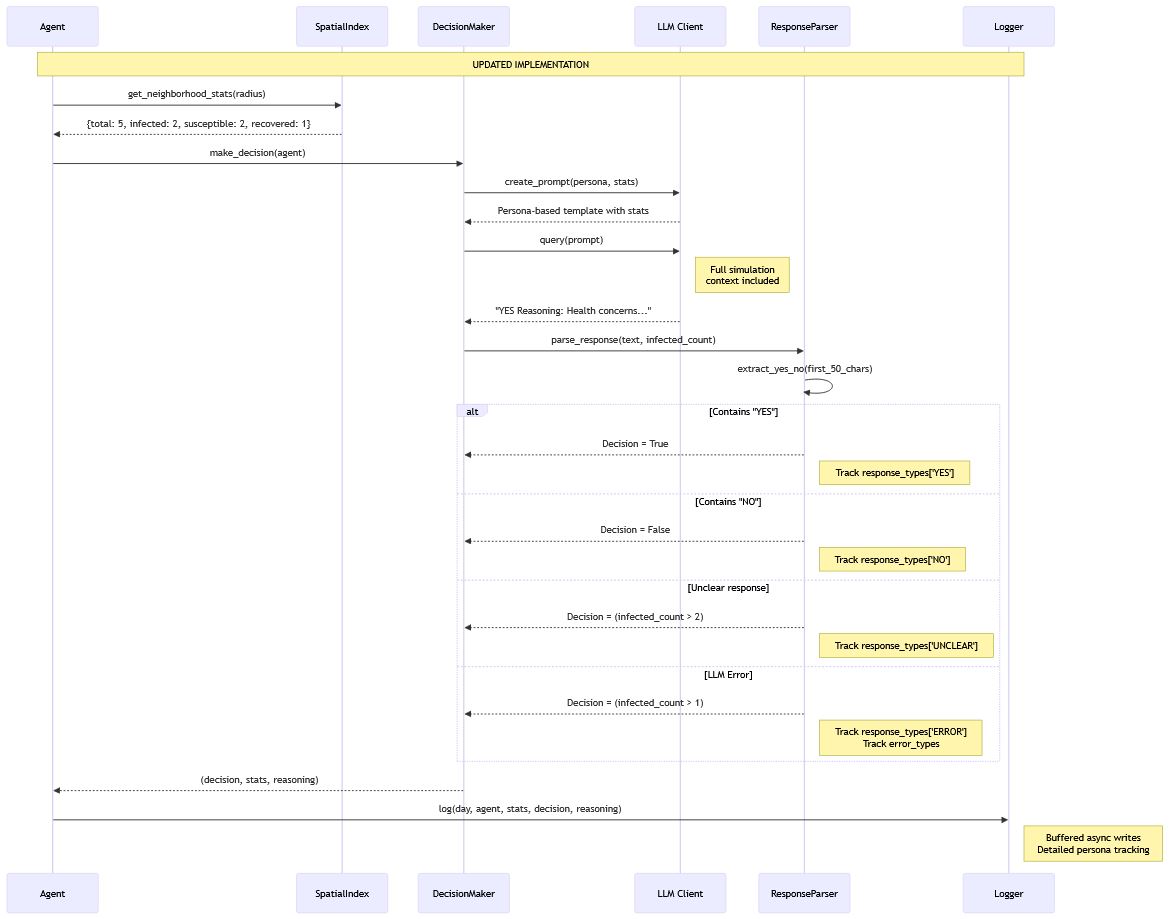

The following sequence diagram shows how the system currently operates: |

|

| Click image to enlarge |

The main shortcomings of the current prototype are:

|

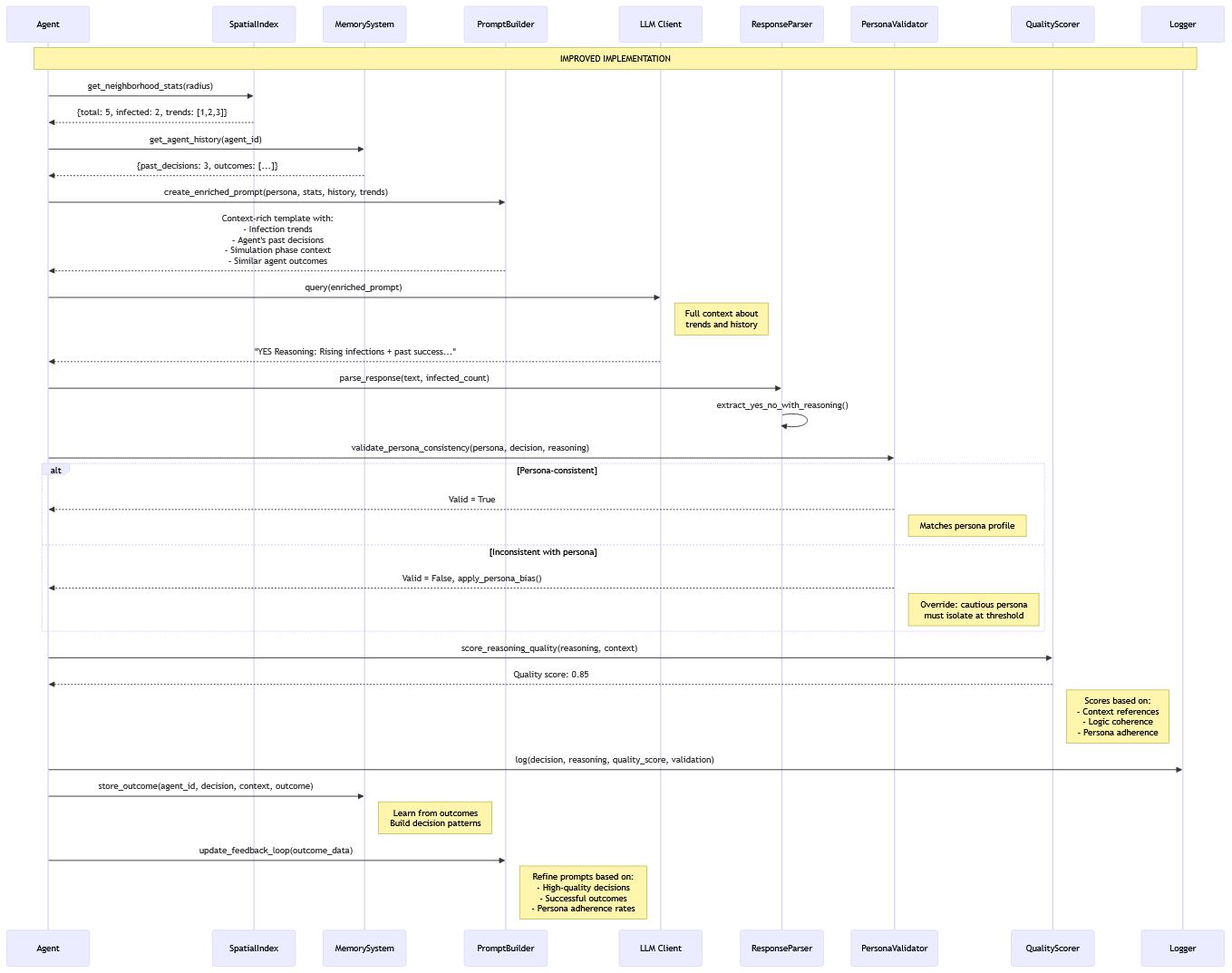

In order to overcome the shortcomings, here are some suggestions for improvements

|

| Of course, such improvements would require more computing power and memory than the current solution. The following sequence diagram shows how such a system might operate: |

|

| Click image to enlarge |

|

In the next post we will see how to develop context-rich prompts and what the impact is in terms of decision quality. It is not as straightforward as you might think!

The VIBE coded SIR prototype ABM Python sourcecode is available on GitHub. |

| Last but Not Least, a Warning |

|

We must maintain a healthy scepticism toward LLMs. Despite their capabilities, they are prone to high hallucination rates and are often disconcertingly good at presenting these fabrications with confidence. While solutions like Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) show promise, the core issue remains: LLMs operate on probability, not true understanding.

Additionally, an often-overlooked aspect is that an LLM's responses are contextual to the entire conversation. If you are debugging code, a crucial best practice is to start a new chat once you have a fixed version. This ensures the model is no longer influenced by the "memory" of your earlier, buggy code, leading to cleaner and more accurate responses. This inherent unpredictability makes the use of good operational practices as well as rigorous verification and validation more important than ever. Do not assume an LLM will correctly handle even simple tasks. Always double-check the output. |

| Back to Top |

| From Rules to Reasoning: Engineering LLM-Powered Agent-Based Models |

| Credits: Concept, draft text, and cross validation by Peer-Olaf Siebers. Advice and copy-editing by Claude Sonnet 4.5 |

| Welcome! |

|

Agent-based simulations have traditionally relied on explicit rule-based logic: agents follow predetermined if-then statements to make decisions. But what happens when we replace these rigid rules with large language models (LLMs) that can reason in natural language about complex scenarios? This shift introduces powerful new capabilities: agents can handle nuanced situations, demonstrate emergent reasoning, and respond to contexts that weren't explicitly programmed. However, it also introduces new technical challenges. Unlike instant rule evaluation, LLM calls require network requests to external servers, taking hundreds of milliseconds per decision. When you have hundreds or thousands of agents, this creates bottlenecks that traditional ABM frameworks weren't designed to handle. This post explores three fundamental concepts for building LLM-powered agent simulations: concurrent processing, decision independence, and context management. Throughout, we'll use Python code snippets to illustrate these concepts in practice, showing how to avoid common pitfalls and design systems that are both realistic and scalable. |

| Use Case: Simulating Disease Spread |

| Imagine simulating a disease outbreak using an SIR (Susceptible-Infected-Recovered) model in a town with 500 residents. Each person needs to decide their daily actions—whether to go to work, stay home, or seek medical care—based on local infection rates, their health status, and personal circumstances. |

|

| The Temporal Ordering Problem |

|

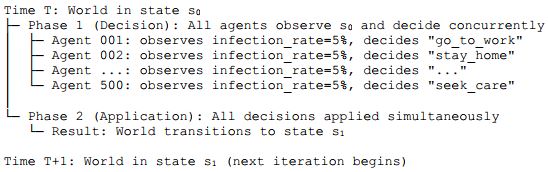

In real life, people make decisions simultaneously based on the same shared reality. To replicate this in our simulation, we must ensure decision independence—all agents observe the same world state when making their choices. If we were to take a purely sequential approach—where each individual makes a decision and immediately updates the world state—we would create an artificial causality chain. The first agent would act based on yesterday's world state, but by the time we reach agent 500, the simulation would have already applied 499 decisions. This introduces temporal ordering bias. In an SIR model, this means that if agent 1 becomes infected and its state is immediately updated, agent 2 now perceives a higher infection rate than agent 1 did, possibly leading it to take more cautious actions such as "stay_home". This artificial dependency on agent ordering distorts the simulation's realism and can lead to systematically biased outcomes that don't reflect how decisions would actually unfold. |

| The Two-Phase Mechanism Solution |

|

To remove this ordering bias, we use a two-phase update mechanism that separates decision-making from decision-application. All agents first decide what to do based on the same snapshot of the world state (Phase 1), and only after every decision is collected do we apply all of them simultaneously (Phase 2). This ensures that all decisions are based on a consistent world view, eliminating the artefact of sequential bias. The solution is a two-phase update cycle: |

|

| This ensures that all decisions are based on a consistent world view, eliminating the artefact of sequential bias. |

| Implementing Concurrency for Rule-Based Agents |

For a traditional rule-based Agent-Based Model (ABM), a synchronous implementation of this two-phase approach looks like this:

Note that whilst this implements the correct logical structure for concurrent decisions, the execution itself is sequential—we process one agent at a time. For fast, rule-based logic where decision-making happens in microseconds, this is perfectly adequate. However, once decision-making involves external calls—such as requests to an LLM API—we need true concurrent execution to avoid unacceptable wait times. |

| Implementing Concurrency for LLM-Driven Agents |

|

The same two-phase structure applies to LLM-driven agents, but the technical implementation must change. The challenge is no longer just logical correctness but managing I/O latency from potentially hundreds of concurrent API calls. Here we use asynchronous programming—a form of concurrency where a single thread can pause (or yield control) while waiting for external operations—such as network requests—to complete. This allows other tasks to continue during that waiting period. In Python, this is implemented with the "asyncio" framework. The following implementation uses "await asyncio.gather()" to run all decision tasks with true concurrent execution: |

| Why Not Use Threads? |

|

It's important to distinguish between asynchronous I/O concurrency and multithreading. Threading runs tasks in parallel using multiple threads within a process, but in Python this introduces complexity and overhead. Since LLM API calls are I/O-bound rather than CPU-bound, multithreading provides little benefit and may even reduce performance due to Python's Global Interpreter Lock (GIL), which prevents true parallel execution of Python code. Asynchronous I/O, in contrast, is lightweight, avoids GIL contention, and scales efficiently across large numbers of agents. The program doesn't waste time waiting—when one request is pending, it immediately starts or continues processing other requests. Only CPU-intensive tasks, such as complex numerical computation or local model inference, justify using threads or multiprocessing. For LLM-driven agents that primarily issue network requests, asynchronous I/O concurrency is the optimal strategy. |

| Managing Server Load with Semaphores |

Firing 500 simultaneous requests at your LLM server will likely crash it with HTTP 503 errors (indicating the server is temporarily overloaded). A semaphore limits concurrent requests:

If you're experiencing constant 503 errors, you can use this concurrent architecture but set "max_concurrent_requests=1". This is not the same as sequential execution. It still maintains the crucial separation between decision and application phases, eliminating temporal ordering bias, whilst preventing server overload. You can then gradually increase concurrency as your infrastructure allows. |

| Robust Error Handling |

Network requests fail. APIs have outages. Timeouts occur. Reliable LLM-driven simulations require robust error handling with retry logic:

|

| Understanding Context Windows |

|

The context window represents an LLM's working memory, measured in tokens. For English text, one token typically represents between 0.5 and 1.3 words, depending on the tokeniser and text complexity (technical terms often require more tokens than common words). Typical context capacities range from 4,096 to 128,000 tokens. This limit encompasses both the input prompt and the generated response. Crucially, the context window operates on a per-request basis rather than per agent. Each time an agent calls the LLM (for example, using "await self.llm_client.generate(prompt)"), the model processes that specific request independently, produces a response, and then discards all information from that interaction. There is no persistent memory between calls—each request begins with a completely blank state. |

| Designing Self-Contained Prompts |

Since each API call is independent, your prompts must be self-contained. Every decision requires a complete description of the agent's situation:

Note the explicit format instruction at the end—this makes parsing the LLM's response more reliable and handles one of the practical challenges of LLM integration. |

| When Context Windows Become Critical |

|

The design choice between stateless and stateful agents has significant implications for context management: stateless agents, recommended for most simulations, make independent decisions that require only a single prompt within the context window, making them simpler and more scalable, whereas stateful agents, used in complex social simulations, accumulate memory across timesteps, requiring both the current prompt and conversation history to fit within the context window, which introduces the risk of forgetting once the token limit is exceeded and necessitates careful memory management strategies. Such memory management strategies include truncating recent interactions, summarising older history, retaining emotionally or causally significant events, or using vector databases for semantic memory retrieval. For stateful agents, a memory management strategy could look like this: |

| Controlling Randomness in LLM Responses |

|

Unlike rule-based agents that produce identical outputs for identical inputs when using the same random seed, LLMs introduce stochasticity. The same prompt can yield different responses due to the model's temperature parameter, which controls randomness. For reproducible simulations: |

| Validation and Calibration |

How do you verify that LLM agent behaviour aligns with domain expectations? Unlike rule-based models where logic is transparent, LLM reasoning is opaque. Implement these validation practices:

|

| Practical Guidelines |

The following guidelines summarise key best practices for developing robust and scalable LLM-driven agent-based models:

|

| Conclusion |

|

Building LLM-powered agent simulations requires careful consideration of concurrency, context, and control flow. By processing decisions concurrently with proper rate limiting, designing self-contained prompts with robust error handling, and systematically validating agent behaviour, you can create realistic, scalable simulations that avoid common pitfalls. The transition from rule-based to LLM-driven agents isn't just a technical upgrade—it's a paradigm shift that enables simulations of unprecedented behavioural complexity. However, this power comes with responsibilities: managing costs, ensuring reproducibility, and validating that emergent behaviours reflect genuine insights rather than prompt engineering artefacts. The future of agent-based simulation is "conversational" - let's build it together. |

| Back to Top |

| Publication: A Novel Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning System for Trading Strategies |

| Credits: Written by Peer-Olaf Siebers |

|

The paper titled "StockMarl: A Novel Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning System To Dynamically Improve Trading Strategies", authored by Peiyan Zou and Peer-Olaf Siebers, has been presented at the 37th European Modeling & Simulation Symposium (EMSS 2025), which is part of the I3M Conference. The paper deals with the development of StockMARL, an innovative simulation platform that integrates multi-agent modelling with deep reinforcement learning to create adaptive trading strategies. The system enables learning agents to observe and interact with diverse rule-based traders, allowing them to develop resilient and interpretable strategies within dynamic, behaviourally rich market environments. |

|

| Click image to enlarge |

| The paper is based on the BSc dissertation of Peiyan and is available here. The presentation, given at the conference is available on YouTube. The slides are available here. |

| Back to Top |

| PROJECT UPDATE: Streamlining Simulation Modelling with Generative AI |

| Credits: Drafted by Peer-Olaf Siebers; turbocharged and summarised by ChatGPT-5. |

|

Simulation modelling is a powerful tool for exploring complex systems, particularly in Operations Research and Social Simulation. Agent-based modelling allows researchers to capture human decision-making and social dynamics, but its reliance on extensive manual coding creates a significant bottleneck. A University of Nottingham summer internship project, led by Sener Topaloglu and supervised by Peer-Olaf Siebers, investigated how Generative AI can help overcome this barrier. By leveraging Large Language Models (LLMs), the project explored automating the translation of natural language descriptions into GAML scripts for the Gama simulation platform. The approach used prompt engineering and reusable design patterns, aligned with the Engineering Agent-Based Social Simulation (EABSS) framework, to streamline the scripting process and enable model reusability. The feasibility study demonstrated that open-source models like Mistral and Llama can generate useful code. Smaller-scale fine-tuning proved effective, though larger datasets introduced hallucinations. The research also highlighted challenges, including resource limitations, context loss during crashes, and syntactic or logical errors in generated scripts. Despite these hurdles, the project showed that Generative AI can significantly reduce coding effort in simulation modelling. Since the internship has been completed in August 2024 there has been some activities with this project. Sener continued the research in his spare time, focussing on improving reliability, testing the latest LLMs, streamlining scripts, and developing a fully automated pipelines from conceptualisation to implementation. Since the internship concluded in August 2024, further progress has been made on this project. Sener has continued the research in his spare time, concentrating on improving model reliability, experimenting with the latest LLMs, streamlining the EABSS script, and building a fully automated pipeline that connect conceptual design and implementation. Detailed reports documenting the project and its extensions are available here:

|

| Back to Top |

| LLM4ABM Discussion @ The Ethics of LLM-Augmented ABM |

| Credits: Content co-created by the LLM4ABM SIG members. Outlined by Peer-Olaf Siebers. Copy-edited by Claude Sonnet 4. |

| Welcome! |

|

The integration of Large Language Models (LLMs) into Agent-Based Modelling (ABM) is moving faster than our ability to fully grasp its ethical consequences. Researchers are already experimenting with LLM-augmented workflows, yet the community lacks a shared framework for thinking about the risks and responsibilities involved. This makes it urgent to pause, reflect, and start shaping collective guidelines before questionable practices become entrenched. What follows is a glimpse into a lively, and at times chaotic, discussion from a recent LLM4ABM SIG meeting. The conversation moved in many directions, but with Claude's help it has been distilled into clear themes that reveal both the promise and the risks of LLM-augmented ABM. |

|

| Image by Copilot (08/2025) |

| Why Do We Need an LLM4ABM Ethics Framework? |

| ABM has always involved ethical considerations, from how we represent human behaviour to whose voices we include in our models. But the integration of LLMs into ABM research introduces what one ethicist calls "the seduction of the frictionless". This seduction is dangerous. When we use LLMs to simulate stakeholder perspectives, we eliminate the messy, uncomfortable negotiations that define real human relationships. Unlike actual humans who push back, argue, and disagree, LLMs always comply. They will happily play any stakeholder role we assign them, creating an illusion of participatory modelling while actually silencing the very voices we claim to represent. This frictionless interaction risks making us forget that "the worth of a relationship is in the friction"; the challenging process of negotiating different viewpoints to reach genuine consensus. |

| What Do We Mean by Ethics in LLM4ABM? |

|

Ethics in this context operates on two levels. At its core, it is about choice and intentionality, we can only act ethically when we have alternatives and make deliberate decisions about our actions. In ABM research, this translates to ensuring our models do not systematically disadvantage or exclude people, particularly marginalised communities. The framework emerging from recent discussions identifies ethics as both deontological (rule-based obligations like "everyone should be heard") and consequentialist (focusing on long-term impacts rather than short-term gains). Crucially, ethics becomes meaningful only when there are "others" whose rights and perspectives we must protect—whether they are research participants, affected communities, or future generations. |

| Ethical Dimensions Across the ABM Lifecycle |

The ethical risks of LLM integration are not evenly distributed across the modelling process. They concentrate on the initial stages of the ABM lifecycle:

|

| Checklist of Ethical Risks |

As a practical starting point for responsible use of LLM4ABM, the following checklist outlines the core ethical risks that demand our attention and deliberate action:

|

| Next Steps for the ABM Community |

| We need ethical guidelines that acknowledge both LLMs' potential benefits (like protecting participant privacy through synthetic data) and their risks. This means developing transparent declaration standards for LLM use, creating frameworks for validating synthetic data quality, and establishing community norms around responsible AI integration. The goal is not to ban LLMs from ABM research, but to use them ethically, recognising that true innovation comes not from eliminating friction, but from navigating it responsibly. |

| Afterthought |

After we finished our discussion, I continued thinking about the topic and why our conversation felt so scattered. It then dawned on me that we actually have multiple dimensions of ethics that need to be considered separately at each stage of the ABM life cycle:

|

| Back to Top |

| LLM4ABM Discussion @ LLMs and ABMs: Promise, Pitfalls, and the Path to Trust |

| Credits: Credits: Content co-created by the LLM4ABM SIG members. Written by Peer-Olaf Siebers. Copy-edited by Claude Sonnet 4. |

| Welcome! |

|

Large Language Models (LLMs) are increasingly influencing research practices. For those working with Agent-Based Models (ABMs), the key question is how to integrate them effectively. They offer practical support in generating ideas and drafting code, but their use also brings uncertainty and caution. This post presents perspectives on using LLMs as tools that enhance research practices without undermining scientific rigour. The ABM community is at a pivotal moment as LLMs demonstrate unprecedented capabilities in social simulation and computational modelling. Recent discussions in the LLM4ABM SIG reflect both enthusiasm and concern regarding the integration of these models into research workflows. The central question addressed in this post is: Where can these tools provide genuine value, and where might they lead us off course? |

| Exploration versus Explanation |

| Perhaps the clearest boundary is between exploration and explanation. In the early stages of a project, LLMs shine. They can suggest new angles, summarise background material, or help generate initial model ideas. These tasks are creative and low risk, and the speed at which LLMs work makes them useful companions. But the stakes change when it comes to explanation, when we are trying to generate evidence, justify findings, or interpret results. Here, over-reliance on LLMs is dangerous. Their outputs are persuasive but not always reliable. If we mistake fluency for accuracy, we risk misleading ourselves and others. Many in the community agree: LLMs may be powerful for idea generation, but they cannot yet be trusted as evidence-making engines. |

| Trust and Transparency |

| That raises the question of trust. How do we create confidence in when and how these tools are used? The answer will not come from individuals working in isolation. It will require community-wide norms and practices. Other tools went through a similar journey. Calculators and spell checkers were once controversial in academic settings. They only became unremarkable once standards were set for when and how they could be used. LLMs are on the same trajectory. Until they become routine, transparency matters. Researchers have a duty to report how they used them—whether for editing, coding, brainstorming, or interpretation. This is not about shaming anyone, but about making practices visible and building trust. |

| Standards, Ethics, and Practicality |

| Of course, the practicalities matter. Some suggest every paper should include a short acknowledgement describing how LLMs were used. Others even argue for sharing prompts, so results can be reproduced. But would this create needless complexity? Many believe a simpler, lighter-touch approach is more realistic. Ethics are another concern. If LLMs shape research directions, code, or even conclusions, should we treat their influence the same way we treat human collaborators? Should there be explicit ethical guidelines about where they fit in? These questions are unresolved, but they are not going away. |

| Why the Unease? |

| Interestingly, researchers rarely feel nervous admitting they used machine learning in their work. Yet many hesitate to disclose LLM usage. Why the double standard? Perhaps because machine learning is seen as a technical method, while LLMs feel more like intellectual partners—closer to the work of writing and thinking. Whatever the reason, silence will not build confidence. Only openness will. |

| Conclusion |

| For now, the safest position is pragmatic. Use LLMs freely for exploration and brainstorming but be cautious about treating them as sources of evidence. Report their role openly, even if only briefly. Push for simple, shared standards that do not overburden researchers, but still ensure integrity. In time, the unease will fade. Just as calculators and spell checkers became unremarkable, LLMs will eventually find their place in everyday research. The transition will be messy, but the path is clear: cautious experimentation, transparent reporting, and collective responsibility for shaping how these tools are used. |

| Back to Top |

| LLM4ABM: A Forum for Discussing the Role of LLMs in ABMs |

| Credits: Written by Peer-Olaf Siebers. Copy-edited by Claude Sonnet 4 |

|

LLM4ABM is a Social Simulation discussion group founded in 2024 that meets online once a month. We are united by a shared interest in exploring how Large Language Models (LLMs) and Agent-Based Modelling (ABM) interact across the entire simulation study life cycle. Our starting point was a focused discussion on how LLMs might help transform qualitative evidence (interview data, ethnographic insights, case studies, expert knowledge, etc.) into behavioural rules that can be utilised in agent-based models. In practice, our conversations have expanded well beyond this. We often find ourselves debating the broader roles of LLMs within the ABM process, as well as their wider implications for scientific research that is built upon established standards and norms. These threads are not separate, but tightly interwoven, and our discussions tend to move fluidly between them. Along the way, I have been taking notes. With the agreement of the group, I will share some of these reflections as blog posts here. They capture many of the engaging and thought-provoking ideas that would otherwise remain tucked away in my notebook. If you would like to join the discussions, please get in touch, and I will add you to the group. |

| Back to Top |

| Tiya's Student Internship: The Use of LLMs for Social Simulation Development |

| Credits: Written by Peer-Olaf Siebers. Research conducted by Tiya Teshome (University of Leicester) |

|

Introduction In this blog post, I would like to share insights from a recent undergraduate internship project that explored the intersection of Large Language Models (LLMs) and Agent-Based Social Simulation (ABSS). ABSS has emerged as a powerful methodology for modelling complex systems, yet the manual design process remains a significant barrier to accessibility. This project investigated how LLMs can automate and streamline social simulation development, addressing three key research questions through systematic investigation:

1. Comparing LLM Output Quality The first task evaluated four leading LLMs, GPT-4, Claude, DeepSeek, and Gemini, across two distinct prompt types: (1) general use cases, and (2) ABSS specific use cases. Each LLM was assessed for precision, accuracy, and simulation modelling suitability. Results revealed varying strengths: whilst all models generated structured agent-based designs, consistency differed significantly. GPT-4 and Claude demonstrated superior architectural understanding, whilst Gemini excelled at generating visual components for enhanced model realism. Prompt engineering proved crucial, with iterative refinement necessary to achieve consistent, structured outputs suitable for implementation. 2. NetLogo vs Python Implementation Quality The second investigation compared LLM-assisted implementation across NetLogo (an ABSS IDE) and Python using an Epidemic SIR and a futuristic museum model. The NetLogo implementations proved more successful, with LLMs effectively debugging turtle logic and variable usage through targeted feedback. Python development presented greater challenges, with frequent non-existent method calls requiring manual corrections. Whilst LLMs provided valuable architectural guidance, Python's complexity demanded more human intervention than NetLogo's simplified agent-based environment. 3. Streamlit Web Application Development The final component produced a functional prototype using LLaMa 3.3 and Streamlit, enabling non-specialists to convert concepts into structured simulation designs. The application guides users through five modular stages: agent roles, behaviours, environment layout, interaction rules, and simulation measures. Key features include component editing capabilities and structured output generation, successfully democratising access to social simulation design whilst maintaining scientific rigour. Conclusions Overall, this project has been a big success thanks to the hard work of Tiya. The research demonstrates LLMs' potential to enhance social simulation accessibility, though human oversight remains essential for ensuring accuracy and implementation success. Acknowledgement: This internship was sponsored by the Royal Academy of Engineering in collaboration with Google DeepMind Research Ready and the Hg Foundation. |

| Back to Top |

| Publication: Large Language Models for Agent-Based Modelling |

| Credits: Written by Peer-Olaf Siebers |

| The paper titled Large Language Models for Agent-Based Modelling: Current and Possible Uses Across the Modelling Cycle, authored by the LLM4ABM Gang (Loïs Vanhée, Melania Borit, Peer-Olaf Siebers, Roger Cremades, Christopher Frantz, Önder Gürcan, František Kalvas, Denisa Reshef Kera, Vivek Nallur, Kavin Narasimhan, and Martin Neumann) has been accepted for presentation at the Social Simulation Conference 2025 (SSC2025). |

| Abstract: The emergence of Large Language Models (LLMs) with increasingly sophisticated natural language understanding and generative capabilities has sparked interest in the Agent-based Modelling (ABM) community. With their ability to summarize, generate, analyze, categorize, transcribe and translate text, answer questions, propose explanations, sustain dialogue, extract information from unstructured text, and perform logical reasoning and problem-solving tasks, LLMs have a good potential to contribute to the modelling process. After reviewing the current use of LLMs in ABM, this study reflects on the opportunities and challenges of the potential use of LLMs in ABM. It does so by following the modelling cycle, from problem formulation to documentation and communication of model results, and holding a critical stance. |

| Back to Top |

| Publication: Using an AI-powered Buddy for Designing Innovative ABMs |

| Credits: Written by Peer-Olaf Siebers |

| After working on it for more than a year, my paper Exploring Conversational AI for Agent-Based Social Simulation Design has finally been published in the Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation. It explores the use of ChatGPT for conceptual modelling and the co-creation of agent-based models. To promote the paper, I gave a presentation at the LLM4ABM Special Interest Group meeting yesterday. Below, you can find links to the presentation slides, the published paper, and a GitHub Repository containing additional resources. The repository is a dynamic resource and over the summer I will add further examples, an updated script, and other resources. You are welcome to add your examples to the repository as well :-). |

| Abstract: ChatGPT, the AI-powered chatbot with a massive user base of hundreds of millions, has become a global phenomenon. However, the use of Conversational AI Systems (CAISs) like ChatGPT for research in the field of Social Simulation is still limited. Specifically, there is no evidence of its usage in Agent-Based Social Simulation (ABSS) model design. This paper takes a crucial first step toward exploring the untapped potential of this emerging technology in the context of ABSS model design. The research presented here demonstrates how CAISs can facilitate the development of innovative conceptual ABSS models in a concise timeframe and with minimal required upfront case-based knowledge. By employing advanced prompt engineering techniques and adhering to the Engineering ABSS framework, we have constructed a comprehensive prompt script that enables the design of conceptual ABSS models with or by the CAIS. A proof-of-concept application of the prompt script, used to generate the conceptual ABSS model for a case study on the impact of adaptive architecture in a museum environment, illustrates the practicality of the approach. Despite occasional inaccuracies and conversational divergence, the CAIS proved to be a valuable companion for ABSS modellers. |

| Back to Top |

| EABSS-2: A Software Engineer's Approach to Creating Agent-Based Models |

| Credits: Drafted by Peer-Olaf Siebers, turbocharged by ChatGPT-4o |

|

Ever wondered how to build agent-based models the smart way, without the usual headaches? If you are a fan of modelling human behaviour, testing policy impacts, or just love crafting digital societies, then you're going to love what's new in the world of simulation frameworks. Meet EABSS-2, the fresh and improved version of the Engineering Agent-Based Social Simulations (EABSS) framework! We all know that designing agent-based models can be a complex (sometimes messy) process, especially when working in teams. That's where EABSS-2 steps in to save the day. It is more than just a tool; it's a guided workflow that helps both solo and collaborative creators turn great ideas into working simulations with far less friction. Although EABSS-2 is still a work in progress, a preview and supplementary material are already available for those keen to take a first look. The framework's new features are introduced in an upcoming journal paper, which offers a detailed walkthrough of the improvements and a case study showcasing them in action. The official release is planned for December 2025, so stay tuned for more updates. |

So, what's new and exciting in EABSS-2?

|

| Back to Top |

| From Roots to Horizons: The Evolution of My ABM Research Journey | |||

| Credits: Words by Peer-Olaf Siebers. Title crafted by ChatGPT-4o | |||

| My research related to Agent-Based Modelling (ABM) falls under the broader theme of Collaboratively Creating Artificial Labs for Better Understanding Current and Future Human and Mixed Human/Robot Societies. I am a strong advocate for Computational ABM. Initially, my focus was on applying Computational ABM across a wide range of domains (poster 1 from 2012). Subsequently, I concentrated on integrating software engineering methods and techniques to develop conceptual agent-based models (see poster 2 from 2023). My current research explores how large language models (LLMs) can be used at various stages of the ABM study lifecycle (see poster 3 from 2024). For more information, please consult the posters:

| |||

| Back to Top | |||